Climate Action Delayed is Climate Action Denied

Delegates meeting in the Amazonian city of Belém for the annual COP global climate summit have every reason to be gloomy. Governments around the world are racing to water down or backtrack on pre-existing climate commitments. In some countries, this is happening because the far right has come to power. The most notable example here is the US, which under the Trump administration has not only abandoned the talks, but has in some instances bullied other countries into reversing climate action.

Other Governments have scaled back their climate ambition, not because the far right has taken over, but because centrists are trying to prevent their ascension to office. Earlier this year, centrist Prime Minister of Canada Mark Carney abandoned the country’s consumer-facing carbon tax in an effort to shore up support against a right-wing populist opponent. Just last week in the European Parliament, the Centre Right European People’s Party sided with the far right to advance proposals that would do away with an obligation on large companies to prepare climate transition plans.

In the not-too-distant past, most political leaders opposed to climate action would cast doubt on the scientific theory that human activity causes global warming. In February 2015, Republican Senator from Oklahoma James Inhofe famously brought a large snowball onto the floor of the US Senate to ‘disprove’ climate change. Since then, however, only the most ardent opponents of climate action take that line – including, unfortunately, President Trump who in September railed against the climate ‘hoax’ at the UN General Assembly.

More common these days, however, is for politicians to advocate a delay in climate action. Those who lack the brazenness to openly contest one of the most widely accepted findings of modern science can comfortably oppose climate policies by supporting them, but just not yet.

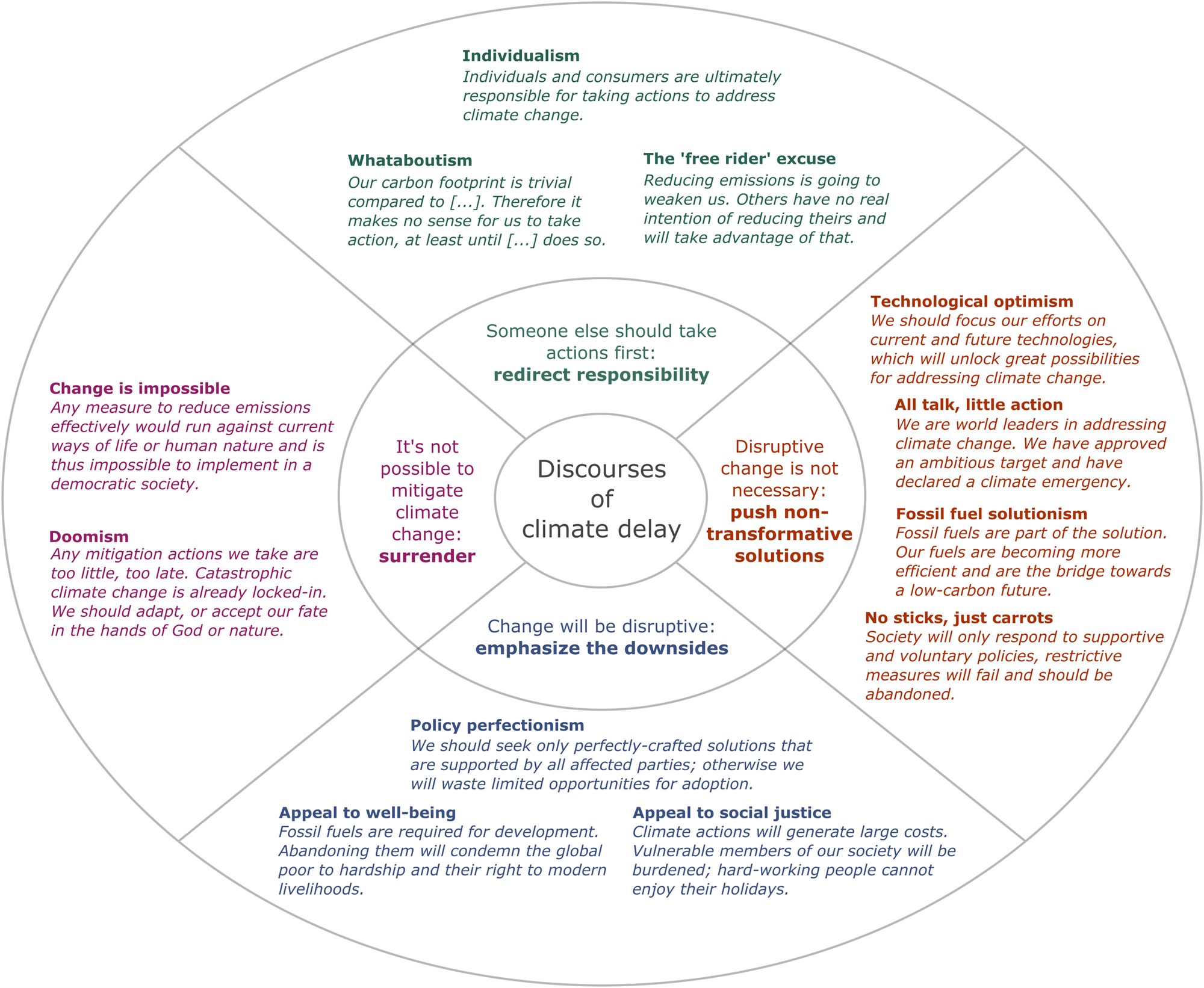

In 2020 a group of German and British experts compiled a typology of ‘discourses of delay’ – i.e., a list of arguments people deploy to put off climate action, set out in the graphic below. These range from redirecting responsibility to someone else (“Ireland is only a tiny country, what about China and India?”), pushing for non-transformative solutions (“We should first switch from oil to gas”), emphasising the downsides (“climate policies will hamper our competitiveness”) and surrendering (“our climate targets were never realistic anyway”).